[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]“Education is teaching our children to desire the right things,” Plato asserted millennia ago. Classical Christian educators, faculty, and parents herald this idea, yet struggle to identify the “right things.” As college applications and standardized tests loom over the Upper School, it’s easy to buy in to the cultural norm that tells us these are the aims of education. However, getting into a good college should not supersede the most important aspect of education: the cultivation of virtue. Classical education trains students to love what lasts. While GPAs lose their significance with every passing year after college, virtuous habits shape students throughout the course of their lives.

Virtue is a nebulous word in today’s culture, yet it should deeply resonate with the Christian. Quite simply, virtue is moral excellence. In Christian theology and in classical education, virtue provides a framework for how to live a flourishing, successful life as ordained by God. Traditionally, there are seven classical virtues from which all others stem. By God’s common grace, Plato, a pagan, systematized the first four, called the cardinal virtues: prudence (wisdom), fortitude (courage), temperance (moderation), and justice. The latter three, the theological virtues, stem from 1 Corinthians 13:13: faith, hope, and love. In my literature classroom, I seek to inculcate these virtues into the culture as I design assessments that develop virtuous habits.

The Enduring Value of a Great Book

The habit of reading good literature forms the human soul. Even books that were not written with a specific moral—and perhaps especially those not written with a specific moral—can be morally formative when the story is told beautifully. In a sense, readers live vicariously through the experiences of the characters. The classical classroom demands that students evaluate the actions and motivations of the characters by means of the seven virtues.

I hope these moments define my students’ memories of my classes. When my former American literature students feel afraid, I hope they call on the example of the runaway slave Jim from Huckleberry Finn who embodies fortitude when he willingly offers up his freedom to save the foolish Tom Sawyer. I hope they hold dear the impression of Santiago’s hope as he sought the marlin in The Old Man and the Sea. Examples such as these provide the students with tangible role models as they emulate Christ in their thoughts and deeds. In addition, I hope my students recall what happens when virtue is replaced by vice. My classical literature students should recall Homer’s Odysseus, a protagonist whose poor example shows us what happens when we act without wisdom: he forsakes his responsibilities as a kingly captain, resulting in the loss of his entire crew. The habit of reading literature well provides students with images of virtue or vice that shape their own view of morality.

Commonplace Books (and Uncommon Wisdom)

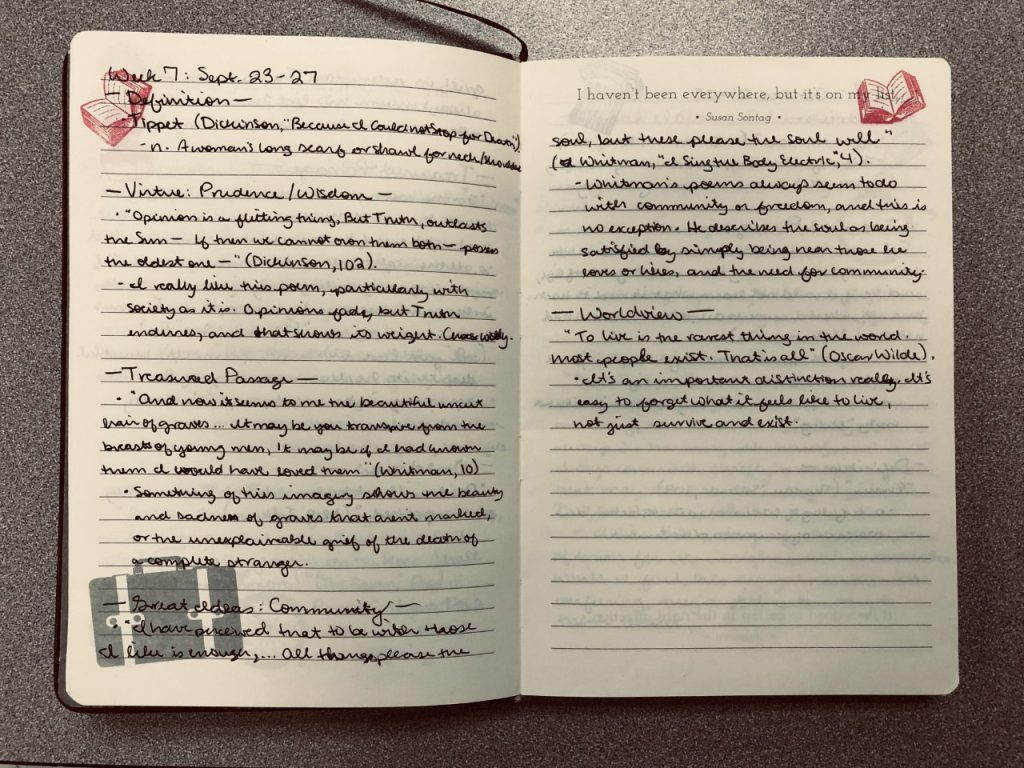

As we teach students to see as desirable the “right thing” of virtue through the medium of great books, their assessments reinforce this labor. In my literature classes, each week students independently record at least five quotes from their reading homework in their commonplace notebooks. A commonplace book is a written storehouse of influential words a reader has encountered. Commonplace books have long been a method of collecting great ideas; the commonplace books of famous writers like John Milton, Thomas Jefferson, and Henry David Thoreau have survived to this day.

For our commonplace books, students collect passages from the books they read that reflect the virtues and vices we study. Not only can a student later reflect on these examples that they’ve collected about the right and wrong ways to live, but recording quotes serves pedagogical purposes as students learn how to read well. The commonplace book serves as a central repository for great ideas and quotes encountered by a reader; in short, it serves as a reader’s memory. It encourages attentive reading as readers actively look for engaging, influential, and beautiful passages and ideas within a book. It empowers a reader to engage with and meditate on passages as he locates them, transfers them from book to book, and sees them topically with other passages from other authors within his commonplace book.

Not only are the students required to seek out and record examples of virtue in their weekly commonplace books, but they meditate upon these treasured passages in their essays and eloquently defend them during their oral quizzes. On tests and papers, they’re asked to analyze the actions of the characters through the lens of the virtue framework. Because assessments communicate the essential information from a course, my literature assessments repeat the theme of virtue.

Reading for a Well-Lived Life

Join me in praying that students will desire to cultivate the virtues as they undertake the hard work of engaging with the reading placed in front of them. As I look upon them daily, I can’t help but contemplate the phrase on the back wall of my classroom that looms over their heads: “Read Well, Live Well.” The well-lived life is the virtuous life. And great books are one of the most effective means of teaching the students how to live well.

Further Reading:

- Karen Swallow Prior, On Reading Well: Finding the Good Life through Great Books

- Josef Pieper, The Four Cardinal Virtues and Faith, Hope, Love

- Peter Kreeft, Back to Virtue: Traditional Moral Wisdom for Modern Moral Confusion

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]